Design Tool and Me

This article is a short collection of reflections by designer nao on how I engage with design tools. Some of it is personal opinion, so take it with a grain of salt.

Days Bound by Powerful Design Tools

In today’s software design industry, it has become mainstream to use powerful design tools like Figma and Sketch, which enable efficient yet flexible UI design. As software products grow in scale, the concept of design systems has emerged—along with specialized tools and functions to manage them.

With the evolution of design tools, our work has become far more efficient. Yet at times, I find myself feeling a certain discomfort toward these very tools.

Take Figma’s Auto Layout feature, for example. Thanks to it, we can now build high-quality layouts quickly and easily, and I benefit from it every day. However, its high degree of freedom can also make other people’s design files difficult to work with.

Moreover, relying too heavily on Auto Layout during the discovery phase can reduce flexibility and slow down iteration. As design tools continue to become more advanced, I suspect we’ll encounter this kind of phenomenon more and more often.

Breaking Away from Figma

In the past few months, I’ve arrived at the conclusion that my ideal balance for UI design is 80% hand-sketching and 20% Figma.

The ratio varies depending on the project, but in general, I rely heavily on sketching by hand. Historically, many designers worked this way before vector-based design tools like Sketch and Figma matured, and even today, some still begin their process with hand sketches.

In my case, I use hand sketching to map out the overall structure of the UI that needs to be considered. (Strictly speaking, it’s not always pen and paper—but the mindset is the same.)

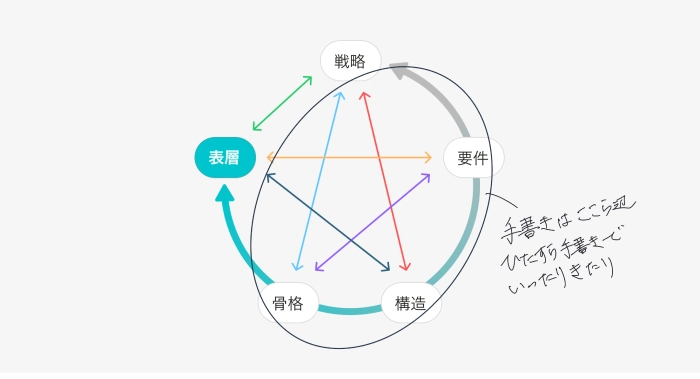

So where does hand-sketching end? To explain this more concretely, I’ll refer to the well-known “Five Stages of Design” model. In my current project, everything up to the stage between skeleton and surface has been completed by hand.

The reasons for this approach—the pros and cons of sketching—will be discussed later. But for me, conducting most of the design process through hand sketches has been incredibly valuable. It helped me redefine the designer’s original role as a form-finder, someone who shapes meaning by discovering structure rather than decorating it.

What “Hand Sketching” Means in the Design Process

Here’s a natural English translation that keeps the reflective tone of the original:

⸻

Here, I’d like to consider why hand-sketching fits so well within the design process.

First, it’s a mistake to think of design as a linear process, or to assume that it must follow a specific framework. Design is, at its core, a constant negotiation with uncertainty — a process of discovering form from high-level abstraction toward concrete expression. If we visualize this through the “Five Stages of Design” model, the path from strategy to surface isn’t a straight line. It’s a series of jumps back and forth between stages, raising the level of concreteness as needed.

(This non-linearity is part of what makes design difficult to grasp — but I see it as an unavoidable truth. The question of how much of this subjectivity should be embraced is something I’ll leave for another time.)

Within this process, the concept of abduction becomes especially important. Designers are ultimately responsible for the final form, so even during creation, we’re constantly hypothesizing what that form might be. We infer the most plausible shape based on constraints and past experience, and then articulate why that form makes sense.

Another key point is how many patterns you can generate. After the structural stage of the design, user stories and use cases are often well defined, but before that, many things remain uncertain. Some argue against exploring UI at this stage, but I take the opposite approach — I actively sketch out many variations by hand.

Facing uncertainty means systematically eliminating less likely possibilities. To do that, you must first surface as many potential forms as you can. Hand-sketching helps immensely here: it allows rapid iteration through a cycle of finding possible forms and reasoning through their logic, all at a speed that digital tools rarely allow.

SmartHR Enables Sketch-First

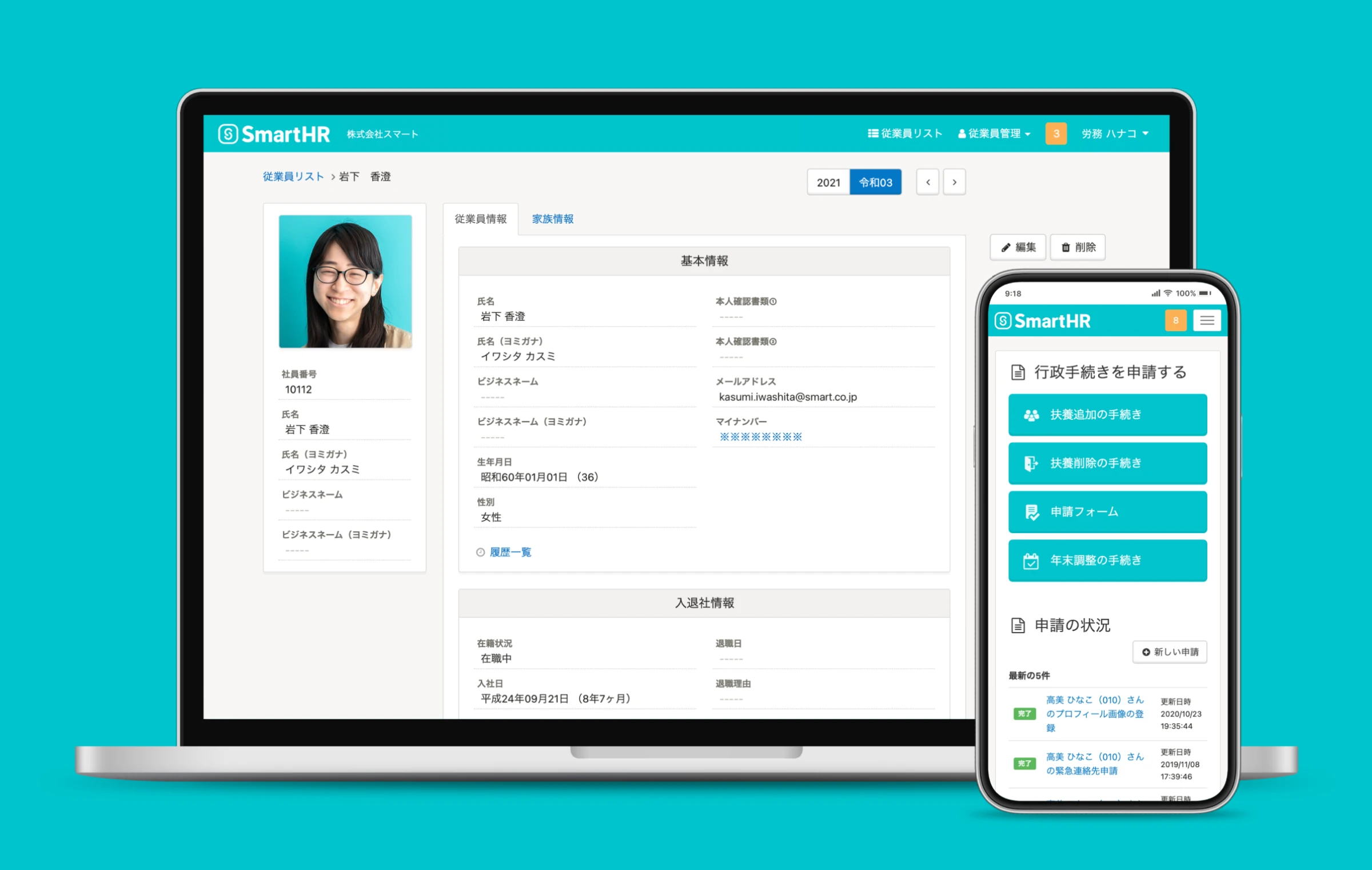

Hand-sketching is an extremely effective design tool—it enables rapid iteration and quick exploration of ideas. However, it isn’t universally applicable. Because sketching inherently strips away detail, it only works well when the team already shares a sufficient common understanding of the product’s form and design principles.

At SmartHR, we have rich design assets such as the SmartHR Design System and SmartHR UI. Since development is built upon these foundations, as long as the team shares a consistent understanding of the underlying principles and components, there’s often no need to visualize everything again using digital design tools.

Conversely, when that shared understanding of form is weak or fragmented, hand-sketching shouldn’t be relied on too heavily beyond the strategy or requirements stages. In such contexts, it can actually make it harder to communicate the intent behind UI design decisions. When choosing to sketch, it’s important to carefully read the situation and judge whether the medium fits the moment.

Why I Don’t Design Every Detail in Design Files

Whenever I explain the intent behind a UI design, I make a point of adding, “This design is still open to change.” Doing so signals that there’s still room for others to participate in shaping it. Team participation in design is essential — and in a large product like SmartHR, it’s nearly impossible for one person to handle all of the UI design alone.

For the same reason, I deliberately avoid making my design files overly detailed. Depending on the situation, I don’t spend much time polishing them. What I need to visualize is only the broad structure; fine-grained UI states or behaviors are often defined by the design system, or tied to data flow — areas where engineers frequently hold deeper insight.

SmartHR also has members familiar with other products. To draw out their knowledge and create better UI together, I intentionally leave space in my designs — not over-designing, so others can think and contribute.

In today’s software design culture, ideas like “Design is too important to be done by designers alone” and “Designing as a team” are becoming mainstream. From that perspective, when designers over-specify design files, they reduce opportunities for others to engage in the creative process — drifting away from a team-based design culture. That’s why I advocate for stepping away from over-reliance on design files.

Yet, Software Design Tools Are Still Necessary

I sometimes hear engineers say they want to “raise their resolution toward the user.” At first, I found this curious — after all, at SmartHR we have plenty of opportunities to interact with users. But after joining the company and starting to write code myself, both for work and personally, I realized something: when you’re deep in code, your attention narrows. You stop seeing beyond what you’re currently implementing. It’s not a flaw — it’s structural. But under those conditions, it’s hard to truly maintain a high resolution of the user, or to keep thinking about how code affects their behavior.

That’s where digital design tools come in. Working within a design tool lets you continuously view the full scope of UI elements that users interact with. You can trace the flow of operations, imagine the surrounding context, and align each interface with the user’s goals — maintaining a sharper sense of the user while designing.

When using graphic tools like Illustrator, you naturally move closer to the screen to check fine detail, and step back to assess overall balance. This rhythm — zooming in and out — parallels the relationship between software design tools and code editors. In design tools, you navigate the macro: how UI connects across products and user journeys. In editors, you handle the micro: data flow and behavior. Alternating between the two creates software that’s both consistent and deeply considered.

Another strength of design tools is their ability to visualize structure. In my current project, I consolidate everything in Figma — design history, conceptual object diagrams, even database table schemas. This allows me to visually verify consistency all the way from the database to the user interface — something only design tools can truly make possible.

Epilogue: Design Tools in the AI Age

Up to now, I’ve written under the assumption of today’s software design environment. But with AI evolving at a visibly revolutionary pace, no one can predict exactly how the design industry will transform. Still, we can make some reasonable guesses.

A few days ago, I came across a tweet that caught my attention.

AIアシステッドな工程を経た制作物に誇りや自尊心を持てるかといった類の話は、20年以上前にPhotoshop等のデジタルツールで(楽をして)作ったものは作品と呼べるのかみたいな議論やSAIの線補正で描いたイラストは自分で引いた線と言えるのかといった議論が散々あった事実だけで十分な説明になってそう

— sabakichi (@knshtyk)

March 11, 2023

I’m not particularly interested in judging the tweet itself, but it prompted me to think about how the shift from analog to digital in design tools compares to the coming shift from non-AI to AI.

In conclusion, I believe designers will continue using conventional design tools for the time being. What will become increasingly important, though, is the concept of direct manipulation of objects. This idea overlaps with UI design theory, but here it carries a slightly different meaning.

When drawing by hand, you express the form you imagine directly through your hand and pen. That directness hasn’t disappeared with the digital transition. Even though the process has become more efficient, we still create, edit, and duplicate objects with our own hands—repeating these actions to move fluidly from the abstract to the concrete, toward an ideal form.

In contrast, today’s AI interfaces rely on prompts—natural-language commands. You can mention color or shape, of course, but there’s no true direct manipulation of form. It’s still an indirect process of altering outcomes through an intermediary: the AI itself.

Furthermore, current AI tools lack strong reproducibility unless one masters prompt engineering. AI outputs what seems most probable based on training data and the prompt provided, which means it can support creative ideation but can’t yet take responsibility for a final product.

For these reasons, I believe the designer’s hands, experience, and judgment will remain vital—at least for now. That said, if AI evolves beyond what we can currently imagine, the story may unfold very differently.

Conclusion

Design tools are incredibly powerful—they let us design UIs efficiently and with precision. But in an era where collaborative design is increasingly essential, that very evolution can become an ironic constraint. As tools grow more advanced, they can unintentionally create friction in teamwork, making collaboration harder instead of easier.

At present, the only real way to prevent this lies in the literacy and awareness of the designers using them—how consciously they choose when and how to rely on tools.

My perspective is just one example, but I hope this reflection offers a moment to reconsider how we relate to our design tools.