The Karma of Being a Designer.

This is a personal monologue written by a designer on the verge of their thirties — a reflection born from personal experience, aiming to update the way designers move and think in their work.

Prologue

I was bored — unbearably bored.

It was two or three months into 2023, and I had already finished most of the UI design work for the product I was responsible for. I couldn’t tell whether it was because I’d gained too much power from years of grueling training, or because the scale of the UI I was designing was as small and trivial as a tutorial-level to-do app. Or maybe it was all thanks to the people around me, and everything I’d achieved was just an illusion. Either way, one fact remained: I was bored. It was March, and the cold still lingered.

Meanwhile, the world around me was changing rapidly as the company grew. In particular, the UI/UX design group I belonged to was shifting away from long-standing commitments to individual scrum teams. Many members were now contributing across multiple products and projects.

I was anxious — deeply anxious.

I had tried committing to multiple products before, but it never worked for me. I simply wasn’t built for it. My personality demands immersion; I can only produce quality work by focusing completely on one thing at a time.

So I strained what little wisdom I had, searching for a way out of this frustration, until I arrived at one conclusion:

Maybe I should just quit design altogether and do something else.

That extreme — almost reckless — thought was tied to a question I had quietly carried for years, one that had never quite left me.

Monologue: The Riddle

I had been at You and I Corporation for nearly three full years. During that time, I’d worked on three product features — yet somewhere inside the development teams, I couldn’t shake off a quiet sense of alienation as a designer.

At the start of each project, I collaborated closely with the PM to understand and define use cases and user stories, then quickly turned those into wireframes and prototypes. That early phase was where a designer’s ability to shape the uncertain into something tangible was truly tested. But once that phase passed, the blueprints I had designed would leave my hands — built by engineers, refined through QA, and released to the world. By then, my involvement naturally shrank, and with it, my sense of belonging. I felt it most acutely during desk checks, bug triages, or production incidents — moments when the design’s influence faded into the background.

For those skilled at contributing across multiple projects, that phase might be a signal — a chance to move on to the next challenge. But for me, who struggles with context-switching, it always felt frustrating. It wasn’t just that I wanted to stay involved — it felt dishonest to step away from something I had helped design. And beyond all that: I was lonely. I wasn’t having fun.

But was this alienation truly something inherent to being a designer? No — I don’t think so. Looking back, I realized I’d taken pride in my obsession with UI design. Yet perhaps that very attachment had blinded me — a convenient excuse to ignore other domains, and a way to justify staying in my lane. Or maybe that’s too harsh. I’ll take that back — I was probably just being unkind to myself.

In the end, I came to see that this sense of alienation was of my own making. I had drawn the boundaries of my role too narrowly and then mourned the walls I built.

And so, this was — in every sense — the karma born of the designer I had been.

I clenched my fists, wiped away my tears, and made a quiet vow: to quit being a designer, and become a developer.

What follows is the record of that vow — a chronicle of conflict and reflection, a struggle against the karmic weight of the word “designer.”

The Battle with the Backend

- The Battle with the Backend

The battle began the moment I faced the backend.

Since joining Yuai Corporation, I had started writing code to bridge the gap between design and engineering. Outside of work, I built native applications, spent spare hours buried in MDN docs, books, and other people’s code. Within the team, with patient help from engineers around me, I slowly began to write code that actually worked — though, of course, at a modest level.

I started from the frontend. For someone who designs interfaces, it was natural to focus on what’s visible and interactive. But the more I wrote, the more I realized how completely I’d been separating frontend and backend in my mind. I won’t pretend to understand the historical reasons behind that divide — I’m not qualified to — but compared to native application development, where the two are less distinct, the split felt strange. Without backend knowledge or experience, even writing frontend code felt like trying to paint without pigment. To design better UI, I needed to understand the backend.

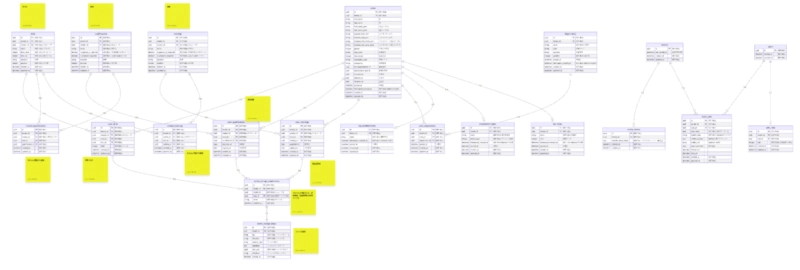

That shift changed how I saw data itself — not as a given, but as a material. In recent years, frameworks like OOUI (Object-Oriented UI) have become mainstream, encouraging designers to identify the key objects that drive a product. But OOUI alone isn’t enough. To truly design the finer details of a UI, what you need is the data model — the database schema that defines what actually exists. So why not design UI directly from the model diagram, without abstracting it away? And why shouldn’t designers take part in shaping that model in the first place?

Fortunately, I had the support of a backend engineer on the same team who welcomed my curiosity. I was even able to contribute — just a little — to model design. We made the ER diagrams visible to everyone in the design tool, and when discussing UI, we referred to those diagrams directly instead of vague conceptual models.

Seeing UI and data intertwined like that was the first time I felt the wall between design and engineering begin to crack.

Through this battle, I came to understand the intersection between design and engineering on a much deeper level. All along, I had been the one drawing the line between them.

And so, my brief encounter with backend coding brought this first battle to a close— though I know that, in truth, this war will go on without end.

The Battle with the Help Desk

The next battlefield I encountered was the help desk — simply called the desk. Some readers might think, compared to the backend, the desk sounds trivial. But the insights it gives to a designer are far greater than one might expect.

I’ll admit it: until then, I had only ever answered when asked on the desk, never taken the initiative to be a first responder. And the requests that came in from customers were incredibly varied — questions about use cases, future roadmaps, and plenty of irregular, unpredictable issues. Most frequently, though, they asked about product specifications.

Working on the desk allowed me to see what customers actually wanted, in far higher resolution. But that wasn’t the only thing it revealed. As I mentioned earlier, learning about the backend gave me enough understanding of the system to answer some specification questions without waiting for the PdE team. When a customer’s need didn’t align perfectly with the existing specs, I could identify the gap from a designer’s perspective and feed that insight back to the team.

If continued, this could form a healthy loop: the desk deepens understanding of real needs, which refines design decisions, which in turn improves the product — and so on.

Simply doing desk work isn’t what matters. What’s powerful is when a designer, while deeply familiar with the product’s specifications, takes part in the desk. That combination holds far more value than I had imagined.

The Battle with QA

QA — Quality Assurance — is the process of identifying bugs after implementation and verifying whether the product truly delivers its intended value. For me, this was an encounter with the unknown. As a designer, I was used to checking the appearance and behavior of features after implementation, but this was my first time conducting full-scale QA for a complex application, including all the edge cases.

To state the conclusion upfront: this battle has only just begun. I still don’t fully understand QA. Yet even so, I’ve already started to see things I never noticed before.

I left the creation of test cases to the dedicated QA specialists, while I focused entirely on performing manual tests. There’s a lot to learn from manual testing itself, but what struck me most was working from someone else’s test cases. If I had written them myself, my perspective would inevitably be biased — shaped by my own design decisions. But when I followed test cases created by another person, I could examine the product from a more neutral and comprehensive viewpoint.

And as expected, not only did I find bugs — I also uncovered areas in the UI that I had overlooked during design.

And as expected, discovering things for myself taught me far more than being taught by someone else. It also made me more fluent in the specifications. At this point, I began to wonder — is there really any reason a designer shouldn’t do QA? If you think about it, testing what you’ve designed with your own hands feels completely natural.

Doing QA also gave me broader ideas about interaction and the overall design process. For example, what if we broke away from the conventional flow of Design → Implementation → QA, and instead tried Design ↔ QA → Implementation? If designers and QA could work together using a shared format before coding even begins, perhaps we could create a workflow that produces high-quality, efficient UI with fewer handoffs. I haven’t considered the practical constraints yet, but it’s worth keeping ideas like this alive.

In conclusion, gaining specialized QA expertise may take significant time and experience, but even just helping with QA can open up a designer’s perspective in valuable ways. It’s an experience I’d genuinely recommend.

The Battle with the Frontend As mentioned earlier, in my pursuit of bridging design and engineering, I began with frontend development — but things didn’t go as smoothly as I’d hoped. It’s not that I couldn’t implement the expected UI behavior on my own; the problem was that I couldn’t write code that balanced scalability and technical debt.

If a designer wants to step into the professional engineer’s arena, they must also learn to write maintainable, production-ready code. I’ve always known that, yet it’s not a skill one can acquire overnight. And when I finally submit a pull request after hours of work, only to receive a flood of review comments and revision requests, I can’t help but feel guilty — as if I’m wasting someone else’s time.

Still, I want to improve the quality of the UI. That tension lingered — until one day, I suddenly realized something: I didn’t actually want my code to be merged.

What I truly wanted was to visualize the designer’s responsibility — to make the intended behavior tangible. Writing code was simply an extension of that purpose.

So when I stepped back and saw things again from a designer’s standpoint, the path became clear: implement things roughly, quickly, and share them early with PdE. If the UI direction seems sound, then we can explore a more maintainable implementation later.

I’m not trying to rewrite the product roadmap or become a full-time engineer. I just want to give the team a visible reference point — a prototype that says, “This is what we mean.” That’s enough.

That said, I know I have to keep striving to write “clean code” myself — and stay committed to that effort going forward.

Design as an Interface?

Continuing this kind of work made me realize something: UI doesn’t just function as the interface between a system and its users — it also serves as an interface for communication among the different roles within a team.

Within SmartHR’s Product Design Group, UI is regarded as a crucial interface in development communication. For more on this perspective, refer to the section titled “UI as an Interface within the Software Development Team.”

Ideas for UI design and hints for improvement are hidden everywhere in the development process.

I’ve long heard the phrase, “Design is too important to be left to designers alone,” and I truly believe it’s true. As that phrase implies, collaborating with experts from other disciplines is essential. But until recently, I think I’d still been treating the boundaries between roles as walls I had to climb over. Through these experiences, I finally realized — I was the one building those walls, and the real challenge is not to overcome them, but to stop creating them in the first place.

If you take that idea to its conclusion, what emerges isn’t a structure centered solely on UI, but a structure where every discipline blends into the others — fluid, continuous, and collaborative.

奇しくも「越境」という表現が、それを言う人がまだ近代から「抜けていない」ことの証明になってしまってる。境を作っているのは誰か。それは本人に他ならない。できる人は境を超えたのではなく、はじめからそれを引いていない。上妻世海氏が言うように「カテゴリーを横断するのではなく縦に貫け」だ。

— Manabu Ueno (@manabuueno)

December 15, 2018

Letting Go of the Obsession with Design

As I mentioned at the beginning, I love UI — I’ve always believed I carried an uncommon passion for it. I’ve long acted as a specialist in UI design, and I’ll continue to think about product experiences starting from the interface. But in the latter half of this term, I found myself — unintentionally — stepping away from deep involvement in design. At first, I worried that this might lower the quality of the work. But that concern turned out to be unfounded. That very choice dissolved the walls between design and other disciplines, and gave those around me more space to engage with design themselves.

There’s a model in design theory called the Double Diamond, which visualizes the cycle of divergence and convergence. If I map my own state onto it, I might be in a phase of divergence now — a period of letting go of my attachment to design that I built up through years of convergence, and instead absorbing new experiences and knowledge. Maybe someday, at another turning point, my perspective on design will shift again, and I’ll return to it with deeper focus and understanding.

But next time, I don’t want to have to “cross boundaries” to collaborate. I want to build a structure where those walls don’t exist at all.

Epilogue

Three months passed in the blink of an eye, and I found myself weighed down — realizing there would be no end to my struggle with the karma of being a designer.

The term is already ending. What will become of me next term? I don’t know, and neither does anyone else — not even I, who no longer have a clear vision of what kind of designer I want to be. But one thing is certain: I will overcome the karma born from the image of “designer” I’ve built up until now, blend into the team as a developer, and continue building products alongside them.

I just want to become stronger — strong enough not to be defeated by the rain, the wind, the tangled domains, or the sudden turns of an organization. And above all, I want to be happy.

Afterword

This story was a work of fiction — but what about you, reading it now? To those who’ve held the same ideas long before this, it may seem naive. To those who disagree with the protagonist, or who dislike essays that dwell too long on ideology, it might feel like something better scribbled on the back of a flyer. Still, if someone out there shares even a fraction of this struggle, and happens to find this page someday — I hope it helps, even a little.

The inspiration for writing this story came from this term’s group goal: “Updating how we contribute to the scrum team.” The group encouraged us to contribute across multiple products, but since that wasn’t exactly my strength — and since I have a bit of a contrarian streak — I decided instead to dive deeply into a single team. That’s where this story began.

When I started, I had no idea where it would lead, but things turned out better than expected. I feel a certain relief — and I think the protagonist of this story, too, would feel grateful for belonging to an organization that gives him the freedom to move as he chooses.